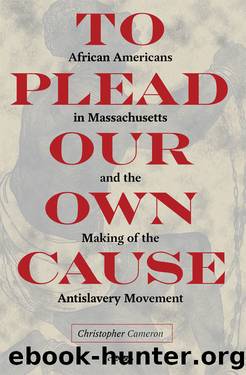

To Plead Our Own Cause by Christopher Cameron

Author:Christopher Cameron [Cameron, Christopher]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, United States, Civil War Period (1850-1877)

ISBN: 9781606351949

Google: R7D_ngEACAAJ

Publisher: Kent State University Press

Published: 2014-01-15T04:15:09+00:00

6

Black Emigration and Abolition

in the Early Republic

In June 1812, Paul Cuffe wrote a letter to British abolitionist William Allen stating that he âthinks well of Establishing mercantile intercourse on the Cours of Africa to Replace to the Africans a trade in Lawfull and Leagull terms in lue of the Slave trade for it seems hard to them to be deprived of all opportunity of gitin goods as usuall.â1 Cuffe was referring to his plans for black Americansâ emigration to Africa, plans that had been in the works for at least four years. Emigrationism, commerce, and abolitionism were intimately linked, he believed, because helping African nations develop legitimate trading alternatives would hasten the demise of the slave trade.2

The black emigration movement during the early nineteenth century served a number of different functions. On the one hand, for activists such as Paul Cuffe and Prince Saunders, it became a way to attack the Atlantic slave trade and provide asylum for those blacks freed from American slavery. African Americans would take specialized commercial and agricultural knowledge to help develop African economies and introduce Christianity to help convert the native inhabitants. They also believed that slaveholders would be more likely to free their slaves if there were a place outside of the United States to send them. On the other hand, black leaders like James Forten pursued emigration schemes in part to deal with the rising level of racism aimed at the free black population during the early republic. This racism manifested itself in the form of riots, efforts to disenfranchise blacks, and laws barring free black emigration to northern states such as Ohio and Pennsylvania.3

Emigrationism represented both a continuation of tactics and strategies that early black activists employed as well as some significant departures that influenced the future course of the antislavery movement in America. Interracial cooperation, institution building, and fostering connections throughout the Atlantic world were central to the work of black emigrationists. In viewing Africa, Haiti, and other regions as asylums for slaves who would eventually be freed, however, Cuffe, Saunders, and other leaders seemingly acquiesced to the gradualist sentiment that often dominated the antislavery ideology of white activists. In this sense, even as these leaders fostered important political connections, emigrationism represented something of a retreat from the radicalism of earlier generations of activists.

Schemes for emigration to Africa, in one form or another, had been present in America since the Revolutionary War. In their April 1773 petition to the Massachusetts General Court, black activists wrote that they desired âas soon as we can, from our joint labours procure money to transport ourselves to some part of the Coast of Africa, where we propose a settlement.â4 That same year Congregational ministers Samuel Hopkins and Ezra Stiles raised money to send two black men, John Quamine and Bristol Yamma, to evangelize in Africa. Yamma and Quamine, members of Hopkinsâ First Congregational Church in Newport, Rhode Island, âwere hopefully converted some years ago; and have from that time sustained a good character as Christians.â5

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| United States | Abolition |

| Campaigns & Battlefields | Confederacy |

| Naval Operations | Regimental Histories |

| Women |

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(3392)

The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution by Walter Isaacson(3247)

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson(2908)

All the President's Men by Carl Bernstein & Bob Woodward(2386)

Lonely Planet New York City by Lonely Planet(2232)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2215)

The Room Where It Happened by John Bolton;(2164)

The Poisoner's Handbook by Deborah Blum(2148)

The Murder of Marilyn Monroe by Jay Margolis(2112)

The Innovators by Walter Isaacson(2111)

Being George Washington by Beck Glenn(2002)

Lincoln by David Herbert Donald(1995)

A Colony in a Nation by Chris Hayes(1941)

Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith by Jon Krakauer(1812)

Amelia Earhart by Doris L. Rich(1705)

The Unsettlers by Mark Sundeen(1696)

Dirt by Bill Buford(1685)

Birdmen by Lawrence Goldstone(1675)

Zeitoun by Dave Eggers(1662)